The Neo-Babylonian Empire

Visit photo

gallery, for further related images

The Chaldeans, who inhabited the coastal area near

the Persian Gulf, had never been entirely pacified by the

Assyrians. About 630 Nabopolassar became

king of the Chaldeans. In 626 he forced the

Assyrians out of Uruk and crowned himself king

of Babylonia. He took part in the wars aimed at the

destruction of Assyria. At the same time, he began to

restore the dilapidated network of canals in the cities

of Babylonia, particularly those in Babylon

itself. He fought against the Assyrian king

Ashur-uballit II and then against Egypt, his

successes alternating with misfortunes. In 605 Nabopolassar

died in Babylon.

Nebuchadrezzar II

Nabopolassar had named his oldest son,

Nabu-kudurri-usur, after the famous king of the second dynasty of

Isin, trained him carefully for his prospective kingship,

and shared responsibility with him. When the father died in 605,

Nebuchadrezzar was with his army in Syria; he

had just crushed the Egyptians near Carchemish

in a cruel, bloody battle and pursued them into the south. On receiving

the news of his father's death, Nebuchadrezzar returned

immediately to Babylon. In his numerous building

inscriptions he tells but rarely of his many wars; most of them end with

prayers. The Babylonian chronicle is

extant only for the years 605-594, and not much is known from other

sources about the later years of this famous king. He went very often to

Syria and Palestine, at first to drive

out the Egyptians. In 604 he took the Philistine

city of Ashkelon. In 601 he tried to push forward into

Egypt but was forced to pull back after a bloody,

undecided battle and to regroup his army in Babylonia.

After smaller incursions against the Arabs of

Syria, he attacked Palestine at the end of 598.

King Jehoiakim of Judah had rebelled,

counting on help from Egypt. According to the chronicle,

Jerusalem was taken on March 16, 597. Jehoiakim

had died during the siege, and his son, King Johoiachin,

together with at least 3,000 Jews, was led into exile in Babylonia.

They were treated well there, according to the documents. Zedekiah

was appointed the new king. In 596, when danger threatened from the east,

Nebuchadrezzar marched to the Tigris

River and induced the enemy to withdraw. After a revolt in

Babylonia had been crushed with much bloodshed, there were other

campaigns in the west.

According to the Old Testament, Judah

rebelled again in 589, and Jerusalem was placed under

siege. The city fell in 587/586 and was completely destroyed. Many

thousands of Jews were forced into "Babylonian exile,"

and their country was reduced to a province of the

Babylonian empire. The revolt had been caused by an

Egyptian invasion that pushed as far as Sidon.

Nebuchadrezzar laid siege to Tyre for 13

years without taking the city, because there was no fleet

at his disposal. In 568/567 he attacked Egypt, again

without much success, but from that time on the Egyptians

refrained from further attacks on Palestine.

Nebuchadrezzar lived at peace with Media

throughout his reign and acted as a mediator after the

Median-Lydian war of 590-585.

The Babylonian empire under Nebuchadrezzar

extended to the Egyptian border. It had a

well-functioning administrative system. Though he had to

collect extremely high taxes and tributes

in order to maintain his armies and carry out his building projects,

Nebuchadrezzar made Babylonia one of the

richest lands in western Asia--the more astonishing because it had been

rather poor when it was ruled by the Assyrians.

Babylon was the largest city of the "civilized world."

Nebuchadrezzar maintained the existing canal

systems and built many supplementary canals,

making the land even more fertile. Trade

and commerce flourished during his reign.

Nebuchadrezzar's building activities surpassed those

of most of the Assyrian kings. He fortified the old

double walls of Babylon, adding another triple

wall outside the old wall. In addition, he

erected another wall, the Median Wall, north of the city

between the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers.

According to Greek estimates, the Median Wall

may have been about 100 feet high. He enlarged the old palace

and added many wings, so that hundreds of rooms with large inner courts

were now at the disposal of the central offices of the

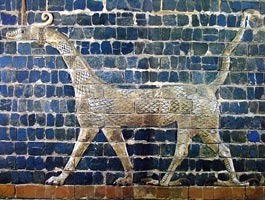

empire. Colorful glazed-tile bas-reliefs decorated the walls. Terrace

gardens, called the Hanging Gardens in later accounts,

were added. Hundreds of thousands of workers must have been required for

these projects. The temples were objects of special

concern. He devoted himself first and foremost to the completion of

Etemenanki, the "Tower of Babel."

Construction of this building began in the time of Nebuchadrezzar

I, about 1110. It stood as a "building ruin"

until the reign of Esarhaddon of Assyria,

who resumed building about 680 but did not finish. Nebuchadrezzar

II was able to complete the whole building. The mean dimensions

of Etemenanki are to be found in the Esagila

Tablet, which has been known since the late 19th century. Its

base measured about 300 feet on each side, and it was 300 feet in height.

There were five terrace like gradations surmounted by a temple,

the whole tower being about twice the height of those of other temples.

The wide street used for processions led along the eastern side by the

inner city walls and crossed at the enormous Ishtar Gate

with its world-renowned bas-relief tiles. Nebuchadrezzar

also built many smaller temples throughout the country.

The last kings of Babylonia

Awil-Marduk (called Evil-Merodach in the Old

Testament; 561-560), the son of Nebuchadrezzar,

was unable to win the support of the priests of Marduk.

His reign did not last long, and he was soon eliminated. His

brother-in-law and successor, Nergal-shar-usur (called

Neriglissar in classical sources; 559-556), was a general who undertook a

campaign in 557 into the "rough" Cilician land, which may

have been under the control of the Medes. His

land forces were assisted by a fleet. His

still-minor son Labashi-Marduk was murdered not long

after that, allegedly because he was not suitable for his job.

The next king was the Aramaean Nabonidus

(Nabu-na'ihc 556-539) from Harran, one of the most

interesting and enigmatic figures of ancient times. His mother,

Addagoppe, was a priestess of the god Sin in

Harran; she came to Babylon and managed

to secure responsible offices for her son at court. The god of the moon

rewarded her piety with a long life--she lived to be 103--and she was

buried in Harran with all the honors of a queen in 547.

It is not clear which powerful faction in Babylon

supported the kingship of Nabonidus; it may have been one

opposing the priests of Marduk, who had become extremely

powerful. Nabonidus raided Cilicia in

555 and secured the surrender of Harran, which had been

ruled by the Medes. He concluded a treaty of

defense with Astyages of Media

against the Persians, who had become a growing threat

since 559 under their king Cyrus II. He also devoted

himself to the renovation of many temples, taking an especially keen

interest in old inscriptions. He gave preference to his god Sin

and had powerful enemies in the priesthood of the Marduk

temple. Modern excavators have found fragments of propaganda poems

written against Nabonidus and also in support of him.

Both traditions continued in Judaism.

Internal difficulties and the recognition that the narrow strip of land

from the Persian Gulf to Syria could not

be defended against a major attack from the east induced Nabonidus

to leave Babylonia around 552 and to reside in

Taima (Tayma') in northern Arabia. There he

organized an Arabian province with the assistance of

Jewish mercenaries. His viceroy in Babylonia

was his son Bel-shar-usur, the Belshazzar

of the Book of Daniel in the Bible.

Cyrus turned this to his own advantage by annexing

Media in 550. Nabonidus, in turn, allied

himself with Croesus of Lydia in order

to fight Cyrus. Yet, when Cyrus attacked

Lydia and annexed it in 546, Nabonidus

was not able to help Croesus. Cyrus bode

his time. In 542 Nabonidus returned to Babylonia,

where his son had been able to maintain good order in external matters but

had not overcome a growing internal opposition to his father.

Consequently, Nabonidus' career after his return was

short-lived, though he tried hard to regain the support of the

Babylonians. He appointed his daughter to be high priestess of

the god Sin in Ur, thus returning to the

Sumerian-Old Babylonian religious tradition. The priests

of Marduk looked to Cyrus, hoping to

have better relations with him than with Nabonidus; they

promised Cyrus the surrender of Babylon

without a fight if he would grant them their privileges in return. In 539

Cyrus attacked northern Babylonia with a

large army, defeating Nabonidus, and entered the city of

Babylon without a battle. The other cities did not offer

any resistance either. Nabonidus surrendered, receiving a

small territory in eastern Iran. Tradition has confused

him with his great predecessor Nebuchadrezzar II. The

Bible refers to him as Nebuchadrezzar in

the Book of Daniel.

Babylonia's peaceful submission to Cyrus

saved it from the fate of Assyria. It became a territory

under the Persian crown but kept its cultural

autonomy. Even the racially mixed western part of the

Babylonian empire submitted without resistance.

By 620 the Babylonians had grown tired of

Assyrian rule. They were also weary of internal struggle. They

were easily persuaded to submit to the order of the Chaldean kings.

The result was a surprisingly rapid social and

economic consolidation, helped along by the fact that after the

fall of Assyria no external enemy threatened

Babylonia for more than 60 years. In the cities the

temples were an important part of the economy,

having vast benefices at their disposal. The business class

regained its strength, not only in the trades and

commerce but also in the management of agriculture

in the metropolitan areas. Livestock breeding [sheep,

goats, beef cattle, and horses] flourished, as did poultry

farming. The cultivation of corn, dates,

and vegetables grew in importance. Much was done to

improve communications, both by water

and land, with the western provinces of the empire. The

collapse of the Assyrian empire had the consequence that

many trade arteries were rerouted through Babylonia.

Another result of the collapse was that the city of Babylon

became a world centre.

The immense amount of documentary material and correspondence that has

survived has not yet been fully analyzed. No new system of law

or administration seems to have developed during that

time. The Babylonian dialect gradually became

Aramaicized; it was still written primarily on clay

tablets that often bore added material in Aramaic

lettering. Parchment and papyrus

documents have not survived. In contrast to advances in other fields,

there is no evidence of much artistic creativity. Aside

from some of the inscriptions of the kings, especially Nabonidus,

which were not comparable from a literary standpoint with those of the

Assyrians, the main efforts were devoted to the rewriting

of old texts. In the fine arts, only a

few monuments have any suggestion of new tendencies.

Visit photo

gallery, for further related images