The Sumerians

Despite the Sumerians' leading role,

the historical role of other races should not be

underestimated. While with prehistory only approximate

dates can be offered, historical periods require a firm

chronological framework, which, unfortunately, has not yet been

established for the first half of the 3rd millennium BC. The basis for the

chronology after about 1450 BC is provided by the data in the

Assyrian and Babylonian king lists, which can

often be checked by dated tablets and the Assyrian lists

of eponyms (annual officials whose names served to

identify each year). It is, however, still uncertain how much time

separated the middle of the 15th century BC from the end of the 1st

dynasty of Babylon, which is therefore variously dated to

1594 BC ("middle"), 1530 BC ("short"), or 1730 BC ("long" chronology). As

a compromise, the middle chronology is used here. From

1594 BC several chronologically overlapping dynasties reach back to the

beginning of the 3rd dynasty of Ur, about 2112 BC. From

this point to the beginning of the dynasty of Akkad (c.

2334 BC) the interval can only be calculated to within 40 to 50 years, via

the ruling houses of Lagash and the rather uncertain

traditions regarding the succession of Gutian viceroys.

With Ur-Nanshe (c. 2520 BC), the first king of the 1st

dynasty of Lagash, there is a possible variation of 70 to

80 years, and earlier dates are a matter of mere guesswork: they depend

upon factors of only limited relevance, such as the computation of

occupation or destruction levels, the degree of development in the script

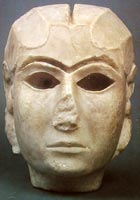

(paleography), the character of the sculpture,

pottery, and cylinder seals, and their

correlation at different sites. In short, the chronology

of the first half of the 3rd millennium is largely a matter for the

intuition of the individual author. Carbon-14 dates are at present too few

and far between to be given undue weight. Consequently, the turn of the

4th to 3rd millennium is to be accepted, with due caution and

reservations, as the date of the flourishing of the archaic

civilization of Uruk and of the invention of writing.

In Uruk and probably also in other

cities of comparable size, the Sumerians led a city life

that can be more or less reconstructed as follows: temples

and residential districts; intensive agriculture,

stock breeding, fishing, and

date palm cultivation forming the four mainstays

of the economy; and highly specialized industries

carried on by sculptors, seal engravers,

smiths, carpenters, shipbuilders,

potters, and workers of reeds and

textiles. Part of the population was supported with

rations from a central point of

distribution, which relieved people of the necessity of providing their

basic food themselves, in return for their work all day and every day, at

least for most of the year. The cities kept up active trade

with foreign lands.

That organized city life existed is demonstrated

chiefly by the existence of inscribed tablets. The

earliest tablets contain figures with the items

they enumerate and measures with the items

they measure, as well as personal names and,

occasionally, probably professions. This shows the purely

practical origins of writing in

Mesopotamia: it began not as a means of magic or

as a way for the ruler to record his achievements, for

example, but as an aid to memory for an administration

that was ever expanding its area of operations. The earliest examples of

writing are very difficult to penetrate because of their extremely laconic

formulation, which presupposes a knowledge of the context, and because of

the still very imperfect rendering of the spoken word. Moreover, many of

the archaic signs were pruned away after a short period

of use and cannot be traced in the paleography of later

periods, so that they cannot be identified.

One of the most important questions that has to be met

when dealing with "organization" and "city life"

is that of social structure and the form of

government; however, it can be answered only with difficulty, and

the use of evidence from later periods carries with it the danger of

anachronisms. The Sumerian word for

ruler, excellence is lugal,

which etymologically means "big person." The first

occurrence comes from Kish about 2700 BC, since an

earlier instance from Uruk is uncertain because it could

simply be intended as a personal name: "Monsieur Legrand."

In Uruk the ruler's special title was "En".

In later periods this word (etymology unknown), which is also found in

divine names such as Enlil and Enki, has

a predominantly religious connotation that is translated,

for want of a better designation, as "en-priest,

en-priestess." En, as the ruler's title,

is encountered in the traditional epics of the

Sumerians (Gilgamesh is the "en of

Kullab," a district of Uruk) and particularly in

personal names, such as "The-en-has-abundance," "The-en-occupies-the-throne,"

and many others.

It has often been asked if the ruler of Uruk

is to be recognized in artistic representations. A man feeding sheep with

flowering branches, a prominent personality in seal designs,

might thus represent the ruler or a priest

in his capacity as administrator and protector of flocks. The same

question may be posed in the case of a man who is depicted on a stela

aiming an arrow at a lion. These questions are purely speculative,

however: even if the "protector of flocks" were identical

with the en, there is no ground for seeing in the ruler a

person with a predominantly religious function.

Literary and other historical sources

The picture offered by the literary tradition of

Mesopotamia is clearer but not necessarily historically

relevant. The Sumerian king list has long been the

greatest focus of interest. This is a literary composition, dating from

Old Babylonian times, that describes kingship (nam-lugal

in Sumerian) in Mesopotamia from

primeval times to the end of the 1st dynasty of Isin.

According to the theory--or rather the ideology--of this work, there was

officially only one kingship in Mesopotamia, which was

vested in one particular city at any one time; hence the change in

dynasties brought with it the change of the seat of kingship:

Kish-Uruk-Ur-Awan-Kish-Hamazi-Uruk-Ur-

Adab-Mari-Kish-Akshak-Kish-Uruk-Akkad- Uruk-Gutians-Uruk-Ur-Isin.

The king list gives as coming in

succession several dynasties that now are known to have ruled

simultaneously. It is a welcome aid to chronology and history, but, so far

as the regional years are concerned, it loses its value for the time before

the dynasty of Akkad, for here the lengths of reign of

single rulers are given as more than 100 and sometimes even several

hundred years. One group of versions of the king list has

adopted the tradition of the Sumerian Flood story,

according to which Kish was the first seat of kingship

after the Flood, whereas five dynasties

of primeval kings ruled before the Flood in Eridu,

Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar,

and Shuruppak. These kings all allegedly ruled for

multiples of 3,600 years (the maximum being 64,800 or, according to one

variant, 72,000 years). The tradition of the Sumerian king list

is still echoed in Berosus.

It is also instructive to observe what the

Sumerian king list does not mention. The list lacks all mention

of a dynasty as important as the 1st dynasty of Lagash

(from King Ur-Nanshe to UruKAgina) and

appears to retain no memory of the archaic florescence of

Uruk at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. Besides

the peaceful pursuits reflected in art and writing, the art also provides

the first information about violent contacts: cylinder seals

of the Uruk Level IV depict fettered men lying or

squatting on the ground, being beaten with sticks or otherwise maltreated

by standing figures. They may represent the execution of prisoners of war.

It is not known from where these captives came or what form "war" would

have taken or how early organized battles were fought. Nevertheless, this

does give the first, albeit indirect, evidence for the wars that are

henceforth one of the most characteristic phenomena in the history of

Mesopotamia.

Just as with the rule of man over man, with the rule of

higher powers over man it is difficult to make any statements about the

earliest attested forms of religion or about the

deities and their names without running the risk of anachronism.

Excluding prehistoric figurines, which provide no

evidence for determining whether men or

anthropomorphic gods are represented, the earliest testimony is

supplied by certain symbols that later became the cuneiform signs for

gods' names: the "gatepost with streamers" for

Inanna, goddess of love and war, and the "ringed post"

for the moon god Nanna. A scene on a cylinder

seal--[a shrine with an Inanna symbol and a

"man" in a boat]--could be an abbreviated illustration of a procession of

gods or of a cultic journey by ship. The constant association of the "gatepost

with streamers" with sheep and of the "ringed

post" with cattle may possibly reflect the area

of responsibility of each deity. The Sumerologist Thorkild

Jacobsen sees in the pantheon a reflex of the

various economies and modes of life in

ancient Mesopotamia: fishermen and

marsh dwellers, date palm cultivators,

cowherds, shepherds, and farmers

all have their special groups of gods.

Just as with the rule of man over man, with the rule of

higher powers over man it is difficult to make any statements about the

earliest attested forms of religion or about the

deities and their names without running the risk of anachronism.

Excluding prehistoric figurines, which provide no

evidence for determining whether men or

anthropomorphic gods are represented, the earliest testimony is

supplied by certain symbols that later became the cuneiform signs for

gods' names: the "gatepost with streamers" for

Inanna, goddess of love and war, and the "ringed post"

for the moon god Nanna. A scene on a cylinder

seal--[a shrine with an Inanna symbol and a

"man" in a boat]--could be an abbreviated illustration of a procession of

gods or of a cultic journey by ship. The constant association of the "gatepost

with streamers" with sheep and of the "ringed

post" with cattle may possibly reflect the area

of responsibility of each deity. The Sumerologist Thorkild

Jacobsen sees in the pantheon a reflex of the

various economies and modes of life in

ancient Mesopotamia: fishermen and

marsh dwellers, date palm cultivators,

cowherds, shepherds, and farmers

all have their special groups of gods.

Both Sumerian and non-Sumerian

languages can be detected in the divine names and place-names. Since the

pronunciation of the names is known only from 2000 BC or later,

conclusions about their linguistic affinity are not without problems.

Several names, for example, have been reinterpreted in Sumerian by popular

etymology. It would be particularly important to isolate the

Subarian components (related to Hurrian), whose

significance was probably greater than has hitherto been assumed. For the

south Mesopotamian city HA.A (the noncommittal

transliteration of the signs) there is a pronunciation gloss "shubari,"

and non-Sumerian incantations are known in the language

of HA.A that have turned out to be "Subarian."

There have always been in Mesopotamia

speakers of Semitic languages. This element is easier to

detect in ancient Mesopotamia, but whether people began

to participate in city civilization in the 4th millennium BC or only

during the 3rd is unknown. Over the last 4,000 years, Semites

(Amorites, Canaanites, Aramaeans,

and Arabs) have been partly nomadic, ranging the

Arabian fringes of the Fertile Crescent, and

partly settled; and the transition to settled life can be observed in a

constant, though uneven, rhythm. There are, therefore, good grounds for

assuming that the Akkadians (and other pre-Akkadian

Semitic tribes not known by name) also originally led a nomadic life to a

greater or lesser degree. Nevertheless, they can only have been herders of

domesticated sheep and goats, which

require changes of pasturage according to the time of year and can never

stray more than a day's march from the watering places. The traditional

nomadic life of the Bedouin makes its appearance only

with the domestication of the camel at the turn of the

2nd to 1st millennium BC.

The question arises as to how quickly writing

spread and by whom it was adopted in about 3000 BC or shortly thereafter.

At Kish, in northern Babylonia, almost

120 miles northwest of Uruk, a stone tablet has been

found with the same repertoire of archaic signs as those

found at Uruk itself. This fact demonstrates that

intellectual contacts existed between northern and southern

Babylonia. The dispersion of writing in an unaltered form

presupposes the existence of schools in various cities

that worked according to the same principles and adhered to one and the

same canonical repertoire of signs. It would be wrong to

assume that Sumerian was spoken throughout the area in

which writing had been adopted. Moreover, the use of

cuneiform for a non-Sumerian language

can be demonstrated with certainty from the 27th century BC.

First historical personalities

The specifically political events in

Mesopotamia after the flourishing of the archaic

culture of Uruk cannot be in pointed. Not until about 2700

BC does the first historical personality appear--historical because his

name, Enmebaragesi (Me-baragesi), was

preserved in later tradition. It has been assumed, although the exact

circumstances cannot be reconstructed, that there was a rather abrupt end

to the high culture of Uruk Level IV. The reason for the

assumption is a marked break in both artistic and

architectural traditions: entirely new styles of cylinder

seals were introduced; the great temples (if in

fact they were temples) were abandoned, flouting the rule of a continuous

tradition on religious sites, and on a new site a

shrine was built on a terrace, which was to constitute the lowest

stage of the later Eanna ziggurat. On the other hand,

since the writing system developed organically and was

continually refined by innovations and progressive reforms, it would be

overhasty to assume a revolutionary change in the population.

In the quarter or third of a millennium between

Uruk Level IV and Enmebaragesi, southern

Mesopotamia became studded with a complex pattern of

cities, many of which were the centres of small independent

city-states, to judge from the situation in about the

middle of the millennium. In these cities, the central point

was the temple, sometimes encircled by an oval boundary

wall (hence the term temple oval); but

nonreligious buildings, such as palaces serving

as the residences of the rulers, could also function as

centres.

Enmebaragesi, king of Kish,

is the oldest Mesopotamian ruler from whom there are

authentic inscriptions. These are vase fragments, one of them found in the

temple oval of Khafajah (Khafaji). In the

Sumerian king list, Enmebaragesi is listed as

the penultimate king of the 1st dynasty of Kish; a

Sumerian poem, "Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish,"

describes the siege of Uruk by Agga, son

of Enmebaragesi. The discovery of the original vase

inscriptions was of great significance because it enabled scholars to ask

with somewhat more justification whether Gilgamesh, the

heroic figure of Mesopotamia who has entered world

literature, was actually a historical personage. The

indirect synchronism notwithstanding, the possibility exists that even

remote antiquity knew its "Ninus" and its "Semiramis,"

figures onto which a rapidly fading historical memory projected all manner

of deeds and adventures. Thus, though the historical tradition of the

early 2nd millennium believes Gilgamesh to have been the

builder of the oldest city wall of Uruk, such may not

have been the case. The palace archives of Shuruppak

(modern Tall Fa'rah, 125 miles southeast of

Baghdad), dating presumably from shortly after 2600, contain a

long list of divinities, including Gilgamesh

and his father Lugalbanda. More recent tradition, on the

other hand, knows Gilgamesh as judge of the

nether world. However that may be, an armed conflict between two

Mesopotamian cities such as Uruk and

Kish would hardly have been unusual in a country whose

energies were consumed, almost without interruption from 2500 to 1500 BC,

by clashes between various separatist forces. The great "empires,"

after all, formed the exception, not the rule.

Enmebaragesi, king of Kish,

is the oldest Mesopotamian ruler from whom there are

authentic inscriptions. These are vase fragments, one of them found in the

temple oval of Khafajah (Khafaji). In the

Sumerian king list, Enmebaragesi is listed as

the penultimate king of the 1st dynasty of Kish; a

Sumerian poem, "Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish,"

describes the siege of Uruk by Agga, son

of Enmebaragesi. The discovery of the original vase

inscriptions was of great significance because it enabled scholars to ask

with somewhat more justification whether Gilgamesh, the

heroic figure of Mesopotamia who has entered world

literature, was actually a historical personage. The

indirect synchronism notwithstanding, the possibility exists that even

remote antiquity knew its "Ninus" and its "Semiramis,"

figures onto which a rapidly fading historical memory projected all manner

of deeds and adventures. Thus, though the historical tradition of the

early 2nd millennium believes Gilgamesh to have been the

builder of the oldest city wall of Uruk, such may not

have been the case. The palace archives of Shuruppak

(modern Tall Fa'rah, 125 miles southeast of

Baghdad), dating presumably from shortly after 2600, contain a

long list of divinities, including Gilgamesh

and his father Lugalbanda. More recent tradition, on the

other hand, knows Gilgamesh as judge of the

nether world. However that may be, an armed conflict between two

Mesopotamian cities such as Uruk and

Kish would hardly have been unusual in a country whose

energies were consumed, almost without interruption from 2500 to 1500 BC,

by clashes between various separatist forces. The great "empires,"

after all, formed the exception, not the rule.

Emergent city-states

Kish must have played a major role

almost from the beginning. After 2500, southern Babylonian

rulers, such as Mesannepada of Ur and

Eannatum of Lagash, frequently called

themselves king of Kish when laying claim to sovereignty

over northern Babylonia. This does not agree with some

recent histories in which Kish is represented as an

archaic "empire." It is more likely to

have figured as representative of the north, calling

forth perhaps the same geographic connotation later evoked by "the

land of Akkad." Although the corpus of inscriptions grows richer

both in geographic distribution and in point of chronology in the 27th and

increasingly so in the 26th century, it is still impossible to find the

key to a plausible historical account, and history cannot be written

solely on the basis of archaeological findings. Unless

clarified by written documents, such findings contain as

many riddles as they seem to offer solutions. This applies even to as

spectacular a discovery as that of the royal tombs of

Ur with their hecatombs (large-scale

sacrifices) of retainers who followed their king and queen to the grave,

not to mention the elaborate funerary appointments with their inventory of

tombs. It is only from about 2520 to the beginnings of the dynasty of

Akkad that history can be written within a framework,

with the aid of reports about the city-state of

Lagash and its capital of Girsu and its

relations with its neighbor and rival, Umma.Sources for

this are, on the one hand, an extensive corpus of inscriptions relating to

nine rulers, telling of the buildings

they constructed, of their institutions and wars,

and, in the case of UruKAgina, of their "social"

measures. On the other hand, there is the archive of some

1,200 tablets--[insofar as these have been published]--from the

temple of Baba, the city goddess of Girsu,

from the period of Lugalanda and UruKAgina

(first half of the 24th century).

For generations, Lagash and

Umma contested the possession and agricultural

usufruct of the fertile region of Gu'edena. To begin

with, some two generations before Ur-Nanshe,

Mesilim (another "king of Kish") had intervened

as arbiter and possibly overlord in dictating to both states the course of

the boundary between them, but this was not effective for long. After a

prolonged struggle, Eannatum forced the ruler of

Umma, by having him take an involved oath to six divinities, to

desist from crossing the old border, a dike. The text that relates this

event, with considerable literary elaboration, is found on the

Stele of Vultures. These battles, favouring now one side, now the

other, continued under Eannatum's successors, in

particular Entemena, until, under UruKAgina,

great damage was done to the land of Lagash and to its

holy places. The enemy, Lugalzagesi, was vanquished in

turn by Sargon of Akkad.

The rivalry between Lagash and

Umma, however, must not be considered in isolation. Other cities,

too, are occasionally named as enemies, and the whole situation resembles

the pattern of changing coalitions and short-lived alliances between

cities of more recent times. Kish, Umma,

and distant Mari on the middle Euphrates

are listed together on one occasion as early as the time of

Eannatum. For the most part, these battles were fought by

infantry, although mention is also made of war chariots

drawn by onagers (wild asses).

The lords of Lagash rarely fail to

call themselves by the title of "ensi", of as yet

undetermined derivation; "city ruler," or "prince,"

are only approximate translations. Only seldom do they call themselves

lugal, or "king," the title given the

rulers of Umma in their own inscriptions. In all

likelihood, these were local titles that were eventually converted,

beginning perhaps with the kings of Akkad, into a

hierarchy in which the lugal took precedence over the

ensi.

Territorial states

More difficult than describing its external

relations is the task of shedding light on the internal

structure of a state like Lagash. For the first

time, a state consisting of more than a city with its surrounding

territory came into being, because aggressively minded rulers had

managed to extend that territory until it comprised not only Girsu,

the capital, and the cities of Lagash and Nina

(Zurghul) but also many smaller localities and even a

seaport, Guabba. Yet it is not clear to

what extent the conquered regions were also integrated

administratively. On one occasion UruKAgina used

the formula "from the limits of Ningirsu [that is, the

city god of Girsu] to the sea," having

in mind a distance of up to 125 miles. It would be unwise to harbour any

exaggerated notion of well-organized states exceeding that size.

For many years, scholarly views were conditioned by the

concept of the Sumerian temple city, which was used to

convey the idea of an organism whose ruler, as

representative of his god, theoretically

owned all land, privately held agricultural land being a

rare exception. The concept of the temple city had its

origin partly in the overinterpretation of a passage in the so-called

reform texts of UruKAgina, that states "on

the field of the ensi [or

his wife and the crown prince], the city god Ningirsu [or

the city goddess Baba and the divine couple's son]"

had been "reinstated as owners." On the other hand, the

statements in the archives of the temple of Baba in

Girsu, dating from Lugalanda and

UruKAgina, were held to be altogether representative. Here is a

system of administration, directed by the ensi's

spouse or by a sangu (head steward of a

temple), in which every economic process,

including commerce, stands in a direct relationship to the temple:

agriculture, vegetable gardening,

tree farming, cattle raising and the

processing of animal products, fishing,

and the payment in merchandise of workers and employees.

The conclusion from this analogy proved to be dangerous

because the archives of the temple of Baba provide

information about only a portion of the total temple

administration and that portion, furthermore, is limited in time.

Understandably enough, the private ector, which of course

was not controlled by the temple, is scarcely mentioned

at all in these archives. The existence of such a sector is nevertheless

documented by bills of sale for land purchases of the

pre-Sargonic period and from various localities. Written

in Sumerian as well as in Akkadian, they

prove the existence of private land ownership or, in the

opinion of some scholars, of lands predominantly held as undivided

family property. Although a substantial part of the population

was forced to work for the temple and drew its pay and

board from it, it is not yet known whether it was year-round work.

It is probable, if unfortunate, that there will never

exist a detailed and numerically accurate picture of the

demographic structure of a Sumerian city. It is

assumed that in the oldest cities the government was in a

position to summon sections of the populace for the performance of public

works. The construction of monumental buildings or the

excavation of long and deep canals could be carried out

only by means of such a levy. The large-scale employment of indentured

persons and of slaves is of no concern in this context. Evidence of male

slavery is fairly rare before Ur III, and even in

Ur III and in the Old Babylonian period

slave labour was never an economically relevant factor. It was

different with female slaves. According to one document,

the temple of Baba employed 188 such women; the temple of

the goddess Nanshe employed 180, chiefly in

grinding flour and in the textile industry, and

this continued to be the case in later times. For accuracy's sake it

should be added that the terms male slave and

female slave are used here in the significance they possessed

about 2000 and later, designating persons in bondage who were bought and

sold and who could not acquire personal property through

their labour. A distinction is made between captured slaves

(prisoners of war and kidnapped persons)

and others who had been sold.

In one inscription, Entemena of

Lagash boasts of having "allowed the sons of Uruk,

Larsa, and Bad-tibira to return to their

mothers" and of having "restored them into the hands" of

the respective city god or goddess. Read in the light of similar but more

explicit statements of later date, this laconic formula

represents the oldest known evidence of the fact that the ruler

occasionally endeavored to mitigate social injustices by means

of a decree. Such decrees might refer to

the suspension or complete cancellation of debts or to

exemption from public works. Whereas a set of

inscriptions of the last ruler from the 1st dynasty of Lagash,

UruKAgina, has long been considered a prime document of

social reform in the 3rd millennium, the designation "reform

texts" is only partly justified. Reading between the lines, it is

possible to discern that tensions had arisen between the "palace"

[the ruler's residence with its annex,

administrative staff, and landed properties] and the "clergy"

[that is, the stewards and priests of the temples].

In seeming defiance of his own interests, UruKAgina, who

in contrast to practically all of his predecessors lists no

genealogy and has therefore been suspected of having been a

usurper, defends the clergy, whose plight he describes

somewhat tearfully.

If the foregoing passage about restoring the

ensi's fields to the divinity is interpreted

carefully, it would follow that the situation of the temple

was ameliorated and that palace lands were assigned to

the priests. Along with these measures, which resemble

the policies of a newcomer forced to lean on a specific party, are found

others that do merit the designation of "measures taken toward the

alleviation of social injustices"--for instance, the granting of

delays in the payment of debts or their outright cancellation and the

setting up of prohibitions to keep the economically or socially more

powerful from forcing his inferior to sell his house, his ass's foal, and

the like. Besides this, there were tariff regulations, such as newly

established fees for weddings and

burials, as well as the precise regulation of the

food rations of garden workers.

These conditions, described on the basis of source

materials from Girsu, may well have been paralleled

elsewhere, but it is equally possible that other archives,

yet to be found in other cities of pre-Sargonic southern

Mesopotamia, may furnish entirely new historical aspects.

At any rate, it is wiser to proceed cautiously, keeping to analysis and

evaluation of the available material rather than making generalizations.

This, then, is the horizon of Mesopotamia

shortly before the rise of the Akkadian empire. In

Mari, writing was introduced at the

latest about the mid-26th century BC, and from that time this city,

situated on the middle Euphrates, forms an important

centre of cuneiform civilization, especially in regard to

its Semitic component. Ebla (and

probably many other sites in ancient Syria) profited from

the influence of Mari scribal schools. Reaching out

across the Diyala region and the Persian Gulf,

Mesopotamian influences extended to Iran,

where Susa is mentioned along with Elam

and other, not yet localized, towns. In the west the Amanus

Mountains were known, and under Lugalzagesi the

"upper sea" [in other words, the

Mediterranean] is mentioned for the first time. To the east the

inscriptions of Ur-Nanshe of Lagash name

the isle of Dilmun (modern Bahrain),

which may have been even then a transshipment point for trade

with the Oman coast and the Indus region,

the Magan and Meluhha of more recent

texts. Trade with Anatolia and Afghanistan

was nothing new in the 3rd millennium, even if these regions are not yet

listed by their names. It was the task of the Akkadian

dynasty to unite within these boundaries a territory that transcended the

dimensions of a state of the type represented by Lagash.

For images, please see our

photo Gallery